By Kim Rendfeld

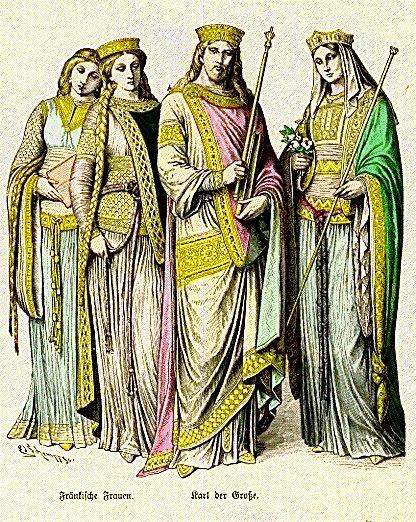

It’s an unlikely love story: a teenager and a 35-year-old widowed father of seven. Child No. 8 with a girlfriend was on the way, and the man was also twice divorced. The teenager is Queen Fastrada, and the much older man is King Charles, whom we today call Charlemagne.

It’s an unlikely love story: a teenager and a 35-year-old widowed father of seven. Child No. 8 with a girlfriend was on the way, and the man was also twice divorced. The teenager is Queen Fastrada, and the much older man is King Charles, whom we today call Charlemagne.

To those who are familiar with Fastrada, she seems to be an unusual choice for the lovers theme. After all, Charles’s biographer Einhard blames her cruelty as the cause of two conspiracies against the king, including one involving Charles’s eldest son, Pepin. Never mind that both sets of conspirators had other reasons to rebel. Or that Einhard never elaborates on what she did. Or that Charles and Fastrada were dead when Einhard wrote those words.

My take on Fastrada is that she was maligned, the victim of a backlash against strong women and the inspiration for my work in progress. Yet the reason I want to write about this queen is her relationship with Charles. Or more accurately, the relationship the sources hint at.

Fastrada’s birth date is not known, but she likely was between the ages of 13 and 19 when she wed Charles in 783, a few months after Queen Hildegard’s death. Charles was still fighting the Saxons, and the probable reason behind the marriage was to solidify a Frankish alliance east of the Rhine, where Fastrada was from.

But there seems to be more than politics in the couple’s union. The 787 entry in the Royal Frankish Annals includes: “The same most gracious king reached his wife, the Lady Fastrada, in the city of Worms. There they rejoiced over each other and were happy together and praised God’s mercy.”

Those two sentences are very unusual for Frankish annals. Most of the time, the authors write about wars and politics. They don’t trouble themselves with how a couple felt about their reunion after months apart. Might Fastrada have been overseeing the annals and making sure they included that information?

Another clue of the affection the couple shared comes from Charles himself in a surviving letter to Fastrada, composed before he went to war with the Avars in 791. Charles greets her as “our beloved and most loving wife.” Perhaps that can be dismissed as a flourish by the person who actually put quill to parchment. (Charles and the vast majority of Franks couldn’t write, but the monarch was among the minority who could read.) Yet the letter gives the impression the greeting is not a mere platitude.

Charles describes the litanies to ensure victory and asks Fastrada to make sure the prayers and rituals are carried out at home, adding that she can decide for herself if she’s well enough to abstain from wine and meat. Gotta like a man who says his wife can make up her own mind.

Then Charles says he is surprised he hasn’t heard from his wife lately. “As to which, it is our desire that you should notify us more frequently concerning your health and other matters.” Not the sentiment of an apathetic husband.

Did Charles and Fastrada’s love survive the heartbreak of his son’s plot to overthrow him? In 794, two years after the conspiracy, the annalists are more concerned with an assembly that Charles held with the pope’s envoys in Frankfurt and the heresy of a cleric named Felix. But the entry also mentions that Fastrada died there and was buried with honors at St. Albans in nearby Mainz.

The rites around Fastrada’s death were similar to those of Charlemagne’s third wife, Hildegard, whom he also loved. Fastrada’s remains were interred within a church – the most desirable of hallowed ground, a monument was dedicated to her, land was donated to the Church on her behalf so that she wouldn’t spend time in purgatory, and Charles commissioned an epitaph. The writer, Theodulf, called Charles “the better part of her soul.”

In this case, “better half” doesn’t mean “superior”; its original meaning is more than half of one’s being such as an intimate friend. So, Theodulf was acknowledging the couple’s close relationship in an age where love was not a requirement for marriage.

Charles and Fastrada’s story shows us love can thrive, even where it seems unlikely.

Sources

Carolingian Chronicles, which includes the Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard’s Histories, translated by Bernhard Walter Scholtz with Barbara Rogers

Charlemagne: Translated Sources, P.D. King

A History of Charles the Great (Charlemagne), Jacob Isidor Mombert

Kim Rendfeld is writing a novel about Fastrada. It will be her third set in eighth-century Francia, joining The Cross and the Dragon (2012, Fireship Press) and The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar (2014, Fireship Press). To read excerpts and the first chapters her published books, visit kimrendfeld.com. You’re also welcome to check out her blog Outtakes of a Historical Novelist at kimrendfeld.wordpress.com, like her on Facebook at facebook.com/authorkimrendfeld