|

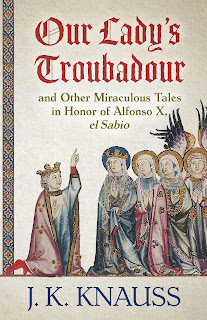

| María de Padilla and Pedro of Castile with María's coat of arms |

By J. K. Knauss

María de Padilla met King Pedro of Castile

during the summer of 1352, when she was eighteen years old, “intelligent,

beautiful, and small in size,” according to contemporary chronicles. The king,

who was also eighteen at the time, recognized in her a kindred spirit, and she

quickly became the love of his life. Although Pedro’s monarch status obliged

him to marry more politically advantageous women, María’s willingness to accept

his love outside the bonds of matrimony earned her an important place in

European history and the royal gene pool. Indeed, it’s difficult to take two

steps in Sevilla and in some parts of Castilla y León today without coming

across a monument dedicated to her, a room she lived in, or a monastery she

founded.

|

| A salon in the King Pedro area of the Royal Palace in Sevilla Photo by J. K. Knauss |

King Pedro (r. 1350–1369) has not one but two

sobriquets recorded in the history books: the Cruel, or the Just. This reflects

the complex panorama of the time. He was loved or hated, but no one was

indifferent to his policies in a war with Aragón, or his stance regarding what

would become the Hundred Years War. These were the early days of sociopolitical

turmoil following the Black Death, which had already devastated the Iberian Peninsula

and would strike again during Pedro’s reign.

María came of noble lineage, and many of her

family members were appointed to high offices at court. It was probably

inevitable that she and the king would meet at some time, but it happened to

occur during a trip the king made to Asturias to deal with Enrique, his

half-brother who would eventually kill him and take the crown, beginning the

Trastámara dynasty.

|

| The Salon of María de Padilla as it was furnished in 1892. Courtesy of pastpictures.org |

Many stories have circulated about the king

marrying María in secret soon after he met her, and later glossing over the

legally valid ceremony because of political pressures to marry Blanche of

Bourbon, first cousin of the King of France. The marriage failed spectacularly,

and a later one was also short-lived and lacking issue. María, on the other

hand, gave Pedro four children: Beatriz, who became a nun at Tordesillas;

Constanza, who married John of Gaunt because King Pedro’s loyalties really lay

with the English; Isabel, who married Edmund of Langley; and a son who didn’t

survive childhood.

Her unsanctioned relationship with Pedro caused

the historians of her time to overlook her accomplishments. While it’s possible

she stayed out of the political arena, it seems unlikely she never told the

king what she thought of any of the volatile issues of his reign. She is on

record as buying expensive properties and founding the convent of Santa Clara

de Astudillo. All of the buildings associated with her feature elegant mudéjar

and Gothic architecture.

|

| The author pretends to be María de Padilla on a hot September day. |

María died at about 27 years of age in 1361,

possibly as a result of plague. Her body was buried in the convent she had

founded. But her remains were soon transferred to join other members of the

royal family in the royal chapel in the cathedral of Sevilla, where they still

rest today. This move could have been motivated by Pedro’s continued devotion, but it was

also strategic in gaining recognition of María’s son, Alfonso, as Pedro’s heir.

In any case, María de Padilla is remembered as Pedro’s queen, in the practical sense if not by

law.

|

| The "Baths of María de Padilla" below the Gothic area of the Royal Palace in Sevilla are actually the rain catchment system. Photo by J. K. Knauss |

Although mostly unappreciated in her time, María’s

story has captivated novelists and artists ever since. A

nineteenth-century opera offers two emotional interpretations of her historical

status. In the first version, which was rejected by censors, María seizes the

crown from Blanche of Bourbon’s head and then commits suicide. In the final

version, Pedro proclaims María as his queen instead of Blanche, and María

perishes from the overwhelming joy of attaining what later critics believe must

have been her most fervent wish.

A

driven fiction writer, J. K. Knauss has edited many fine historical novels and

is a bilingual freelance editor. Her historical epic, Seven Noble Knights, will be released by Encircle Publications December 11, 2020. J. K. Knauss earned a PhD in medieval Spanish with a dissertation on the portrayal of Alfonso X’s laws in the Cantigas de Santa Maria, which has been published as the five-star-rated Law and Order in Medieval Spain. Look for her book based on the Cantigas, coming in 2021. On the

contemporary side, her YA/NA paranormal Awash in Talent was

published by Kindle Press. Find out more about her writing and bookish activities here. Follow her on Facebook and Twitter,

too!